Here’s what we learned from our AFSC training on the key reasons to shut down the Homestead Child Detention facility.

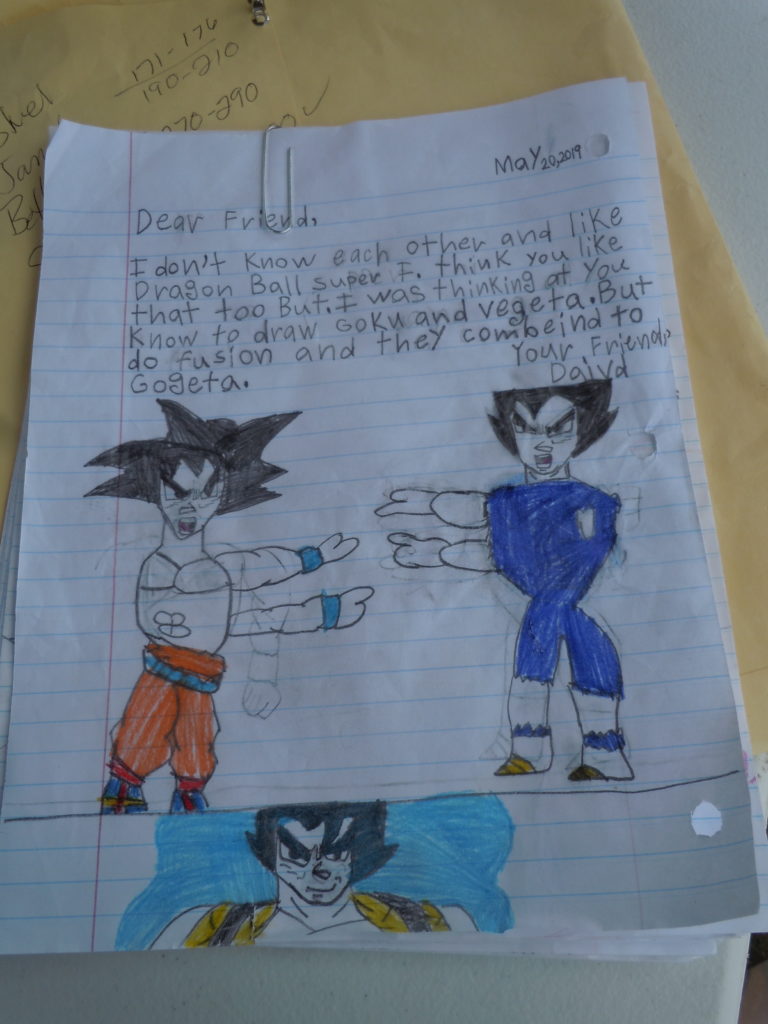

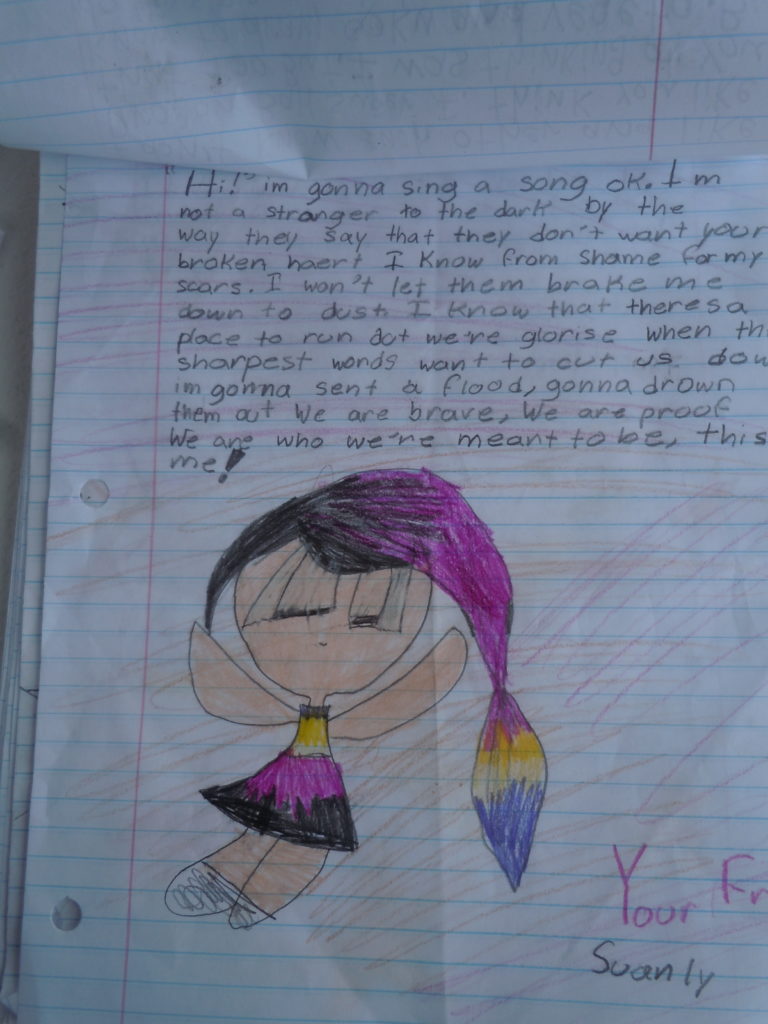

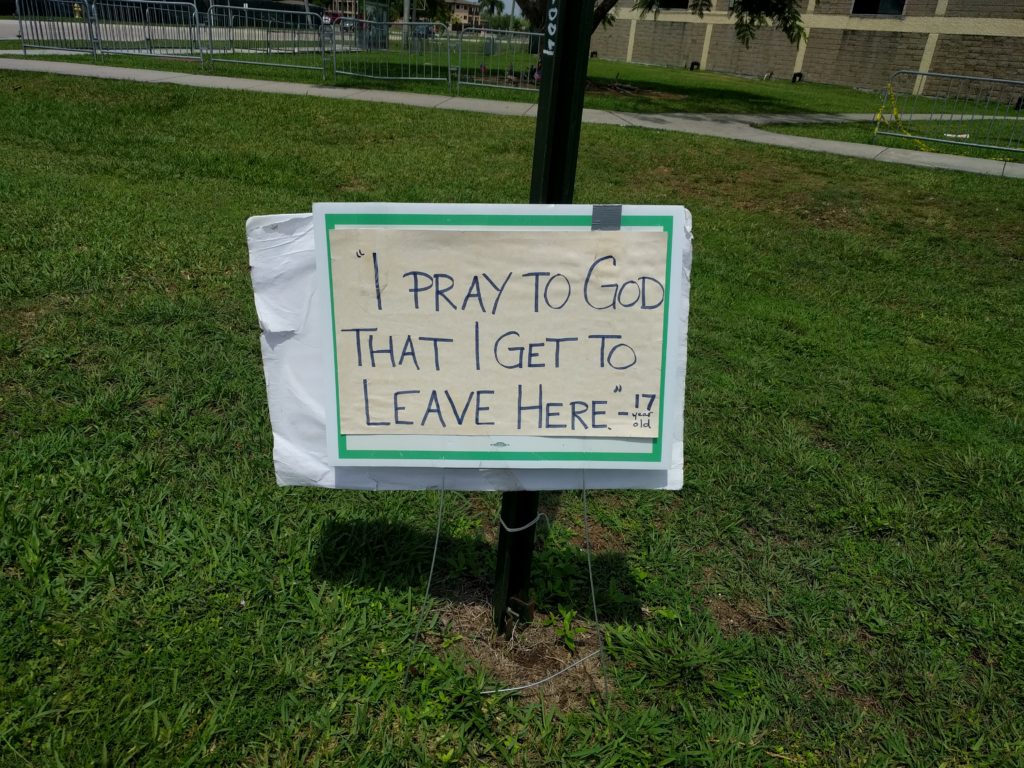

- It is a prison. The individuals who are there asked for asylum at the border, which is their legal right under international law. Yet instead of being immediately released to a sponsor or family member while their cases were processed, they are being held behind high wire-mesh fences, where they are under constant surveillance in facilities with minimal education and recreation. They are not allowed to hug each other, even their siblings.

- This prison is run by a for-profit corporation, which means there is limited accountability. It is also costing tax payers $500,000/day; more than three times the amount it costs to have children in non-profit shelters. And since companies are profiting off incarceration, they have no incentive to limit or reduce the number of people being held. In fact, it is more profitable them to keep increasing the numbers.

- Detaining young people is traumatic and can cause long-term health risks.

- It is in violation of the Flores Settlement Agreement, which mandates that children should be held no more than 20-days. Because this has been designated as an “emergency influx shelter,” children have reported being there as long as 8 or 9 months. We have been told that many children’s reunification paperwork is finished months before the children are finally allowed to leave.

- Undocumented sponsors who try to claim the children risk arrest and deportation because there’s currently an agreement between the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which oversees the children, to share information on potential sponsors with ICE.

- The number of children at the facility keep increasing, leading to worse conditions. Some of the dorms sleep up to 250 children in a single room.

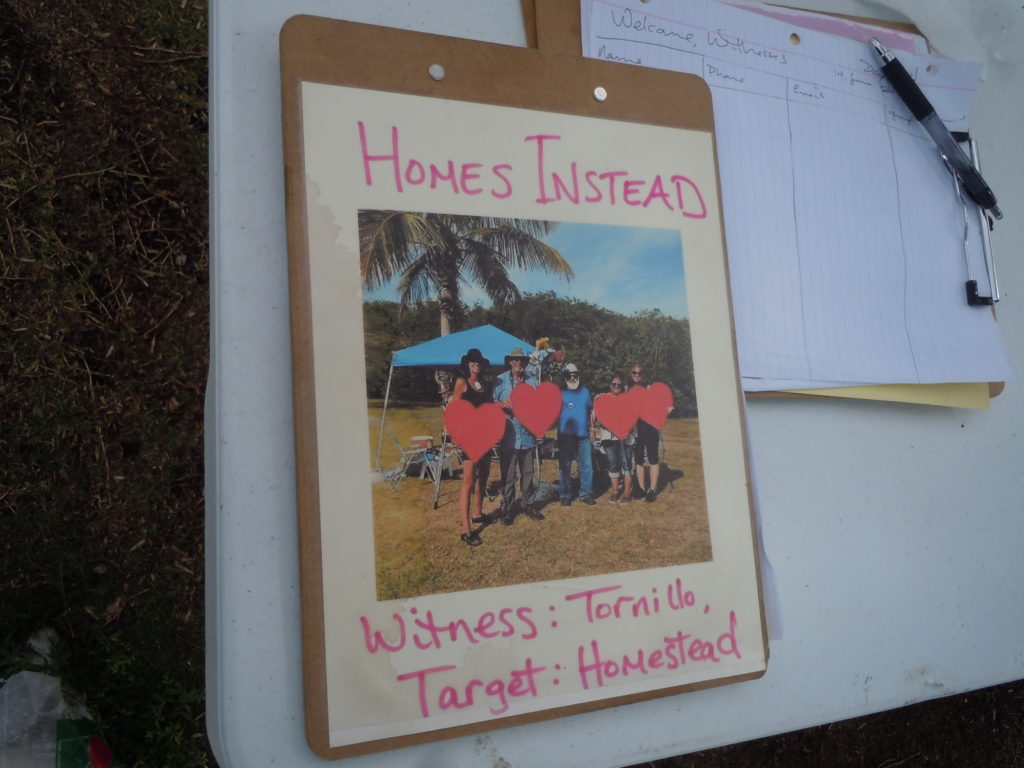

- The people of Homestead want a sustainable economy that bring resources to the community, not jobs that facilitate the abuse and detention of children.

WHAT PEOPLE CAN DO:

- Call your Congresspeople and ask them to pass (HR 1069/S 397) Shut Down Child Prison Camps Act and (S388) the Families Not Facilities Act. These bills would make sure all detention centers complied with the terms of the Flores Settlement Agreement and prevent sharing of information between ORR and ICE.

- Ask your Congresspeople to advocate in every way possible to shut down this facility. Ask them to visit the facility so they can see for themselves what is going on and join the call of three Florida Congresswomen to shut the facility down immediately.

- Let other people know what is going on. Talk to at least 5 friends, write a letter to the editor, discuss this issue with faith or activist groups you might be involved with. For resources, check out http://stopchilddetention.org.

- Divest and put pressure on companies that are directly or indirectly contributing to child detention. You can get more information at http://investigate.afsc.org/

- Ask Democratic candidates to take the pledge to visit the Homestead Detention Facility while they’re in Miami for the debates. (Even if they’ve already taken the pledge, you want to make sure that they’re aware that you care about this issue. You also should follow up with them to make sure that they actually come.)